In 2014, Kalyb Wiley Primm, a seven-year-old Black boy with a hearing impediment in Kansas City, broke down in tears after he was bullied by a fellow student. Upon hearing the little boy’s cries, his school’s resource officer, Brandon Craddock, embarked on an intervention. Frustrated by Kalyb’s persistent yells of distress, his efforts to calm him foiled, the officer attempted to remove the second-grader from the classroom for a visit to the office of the principal, Ann Wallace.

What happened next is the subject of a lawsuit recently filed by the American Civil Liberties Union against the Kansas City public schools, Craddock, and Wallace: Kalyb’s arms were twisted behind his back, and he was handcuffed, in violation of his constitutional rights against unlawful seizure and excessive force.

This is not an anomaly. As the nation’s wrenching conversation about race continues, attention is shifting inexorably downward—to the youngest victims of profiling and stereotyping.

Last month, the Yale Child Study Center released a research brief with the unwieldy title, “Do Early Educators’ Implicit Biases Regarding Sex and Race Relate to Behavior Expectations and Recommendations of Preschool Expulsions and Suspensions?” Leading the authors was psychologist Walter S. Gilliam, well known for his research on preschool expulsion, which had its official rollout in 2005. Long before Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, and Patrice Cullors, created Black Lives Matter, “an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise.”

Gilliam’s early work revealed that preschool children were expelled at a rate more than three times that of older students in kindergarten through 12th grade. Among his other findings: four-year-olds were expelled at a greater rate—roughly 50 percent—than three-year-olds; rates for boys were much greater than those for girls; and African-American children were about twice as likely to be expelled as Latino and Causasian students, a rate that more than doubled relative to Asian-American prekindergarteners.

“Expulsion is the most severe disciplinary sanction that an educational program can impose on a student,” Gilliam wrote. Under the section dedicated to implications for policy, he recommended support services for children with severe behavioral challenges (italics, mine) as well as training for those working with these children in early childhood programs.

A decade later, in 2015, Sara Neufield, a contributing editor to the Hechinger Report, would write that Gilliam’s research “shocked the nation.” I’m not so sure of that. But his data did spark a conversation in the slow-moving, cautious circles of policymaking. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights reported that while Black children represented fewer than one in five preschool students, they comprised almost half of those who received multiple out-of-school suspensions.

The subject also piqued the interest of early childhood educators, on the front lines of this phenomenon.

In Gilliam’s latest research, he and his team studied preschool teachers’ implicit bias as a factor in expulsion. In the first task, the investigators told the participants, all recruited at an annual conference for early educators, that they would be viewing some video segments that might contain challenging behaviors. They then tracked their eye movements as they gazed at a dozen 30-second clips. But there were no such behaviors—a deception devised to probe unconscious bias.

“What we found was exactly what we expected based on the rates at which children are expelled from preschool programs,” Gilliam crowed, delivering his soundbite to NPR’s Cory Turner upon release of the study. “Teachers looked more at the black children than the white children, and they looked specifically more at the African-American boy.”

The team also recorded responses to a vignette depicting a preschool child with so-called behavioral challenges—among them difficulty napping and following instructions, hitting or pushing. (Difficulty napping? Really? And pushing? Does anyone around here know a four-year-old boy?) In any event, they manipulated gender and race by assigning stereotypical names—Latoya, Emily, DeShawn, Jake—and asked teachers to rate the severity of the behavior on a scale of one to five.

Next, the participants were asked to assess how overwhelmed they felt, with the help of a “hopelessness” subscale of the Preschool Expulsion Risk Measure. White teachers held Black students to a lower standard, consistent with previous research that documented a shift in expectations based on stereotypes and implicit bias. The bottom line: those who believed the child was likely to behave badly, would be less surprised, and their rating less severe.

Some participants in the Yale study were given background information about the “disruptive” child’s home life, a portrait of turbulence, parental inconstancy, maternal depression, and financial insecurity. Sadly, but not in the least surprising, teachers’ empathy extended to children of the same race, their ratings of severe behavior skyrocketing for those who were different.

Gilliam and his team were not able to document a relationship between a child’s gender and race and teachers’ recommendations to expel or suspend. Black teachers, they found, held students to a higher standard, rating their behavior more severely than that of white children. They also proposed harsher “disciplinary exclusion” than did white educators—regardless of race.

Based on the data on expulsions and suspensions in kindergarten through 12th grade, the team hypothesized that Black early educators serving communities with students of color in low-income families would have less access to needed resources, such as mental health services and trauma-informed care. It’s true that in our deeply segregated public school system, resources are scarce—the byproduct of historic institutional racism. Black and white educators are collapsing under the weight of student need, and the kinds of supports for which Gilliam has long advocated are critical, especially for our youngest children and those who care for and educate them.

But the problem is complex, infused with assumptions that are also linked to cultural and racial biases. An ethnographic study by Franita Ware, reported in the journal of Urban Education, suggests another wrinkle. In her article, Ware mourns the loss of a historical model of black teaching, highlighting two practitioners of warm-demander pedagogy. Rooted in an ethic of caring and responsiveness, these educators “provide a tough-minded, no-nonsense, structured and disciplined classroom environment for kids whom society had psychologically and physically abandoned.”

Although Gilliam’s contributions to the data base on preschool suspension and expulsion are noteworthy, his latest research betrays a disturbing clinical detachment—and hubris. I almost didn’t make it past the first sentence: “Preschool expulsions and the disproportionate expulsion of Black boys have gained attention in recent years, but little has been done to understand the underlying cause behind this issue.” What about all the other research that’s emerged, some of it cited by the authors? Including that of psychologist, Andrew Todd, and his team at the University of Iowa, who found that the faces of black boys as young as five trigger thoughts of guns and violence.

And what about the children?

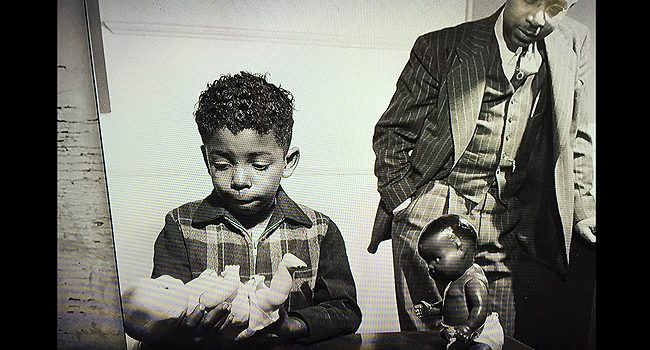

In the 1940s, Kenneth and Mamie Clark, the first African-Americans to obtain their doctoral degrees in psychology from Columbia University, designed and conducted a landmark study to determine children’s racial perceptions. Using four dolls, distinguished only by their color, the Clarks asked their subjects—ranging from three- to seven-years-old—to identify both the race of the doll and the color they preferred. A majority of the children preferred, and assigned positive characteristics to, the white doll.

The findings of the study, done fourteen years before Brown v. Board of Education, would be used as testimony in the landmark case. But as Kenneth Clark told an interviewer for “Eyes on the Prize,” a 14-hour documentary on America’s 20th-century civil rights movement aired on PBS in 1987 and 1990, “we did not do it for litigation. We did it to communicate to our colleagues in psychology the influence of race and color and status on the self-esteem of children.”

This is the heart of the matter.

I have images on my computer of disabled children of color handcuffed. Why in the name of the gods would anyone do this. I am thankful that we humans are not immortal, because the image seared into my brain will never leave until the final sweet act of death is visited on me.Shame on us! Shame on us!

When will the United States Department of Education protect the self-esteem of Bold Brilliant Beautiful Black Boys? I have witnessed each of my son’s Black male friends pre-k smiles turn into elementary school tears and their spirit of leadership turn into dark clouds of depression. Every therapist says it is not our Black boys and our sons must learning coping skills. Why must a five-year-old Black boy learn to cope with bigotry?

Education systems seemingly don’t care, because the damage is not physical. Everyday we are on the battlefield for our sons. We weep for our boys, because the poetry of Rev. William Holmes Borders, ” l Am Somebody”, and other Civil Rights messages that our parents gave us, just are not saving our sons.

We took our boys out of private schools or the public gifted schools and placed our sons in schools for Black Boys.

Sadly, a child must be placed in handcuffs for there to be a response. At that point a a Black boy’s spirit is shattered. Thus, at an early age, Black boys are robbed of their potential and dreams. That is America’s Cradle-to-Prison Pipeline.

We thank God our son is healing, along with three of his friends, at George Jackson Academy. Parenting once again, is a joy!